This chapter presents the specifics of operational planning for public health authorities in case of biological emergencies, and introduces some principles.

In Germany, responsibility for drawing up operational plans for biological emergencies rests with the national government, federal states (regions) and municipalities. There are no standard rules for drawing up these plans. However, there are framework plans at national level, e.g. Influenza pandemic planning, and Supplements to the national pandemic plan – COVID 19 – new coronavirus disease or Suspected cases of Ebola. These were drawn up by the Robert Koch Institute in consultation with other bodies.

Apart from this, the (higher) regional health authorities in some federal states have drawn up plans for viral haemorrhagic fever (VHF), infection alert plans and plans for high consequence infectious diseases (HCID). All federal states have drawn up plans for influenza pandemics. In addition, the ministries of the interior in the federal states have produced alert and operational plans for disaster risk management. All of these plans can serve as a basis for specific plans at regional level.

Operational plans for crisis situations often take the form of legal regulations. When operations are underway these are difficult to read, and they are not structured as they would need to be for application in the field. Often no electronic systems are used to draw the operational plans. Creating and maintaining them by hand is a time-consuming process. Updating them is therefore costly. As a result the plans are not always up-to-date.

The staff involved need to be familiarised with the content of the plans through training before operations take place, and if possible should first be able to try things out in drills.

N.B.: Plans can only be successfully implemented if content is regularly updated and users are trained to apply it.

Objectives of successful operational planning

An operational plan should describe possible measures that need to be implemented by the staff of a public authority in a special situation, e.g. the hazards that arise in case of an epidemic.

Operational plans must contain up-to-date information, be self-explanatory and have a uniform structure. Complicated and poorly structured plans are not fit for purpose. In practice, checklists and flowcharts have proven helpful as they make it easier to understand the processes, and provide rapid orientation during a crisis.

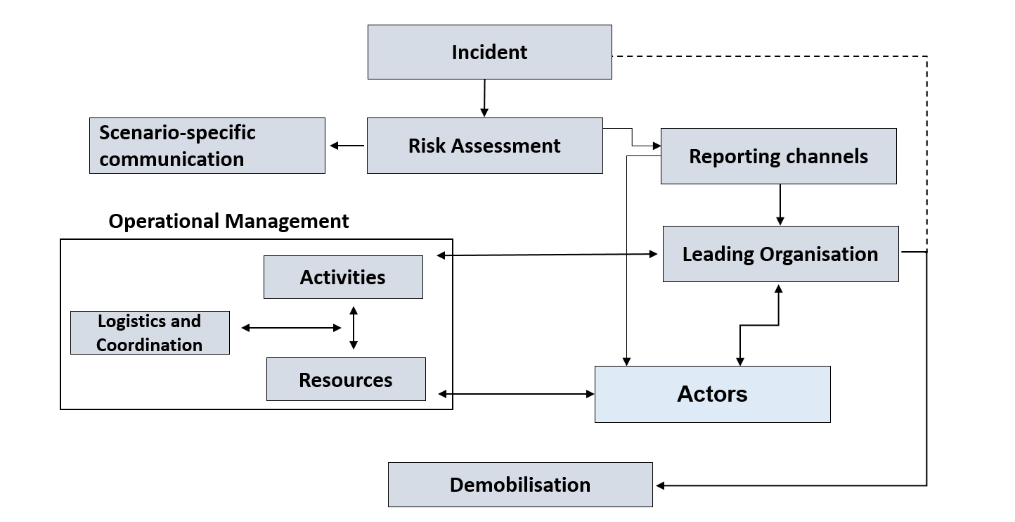

Structuring operational plans as shown below has proved successful:

The graphic shows individual points in an operational plan in the form of a flow diagram. The points can be used to structure an operational plan.

An explanation of each point is given below.

Risk assessment

In addition to the general risk assessment that (sub-regional) administrative districts/independent cities or federal states (regions) are obliged to carry out in the context of population protection, the responsible public health offices should conduct a corresponding subject-specific risk assessment for their region as a precautionary measure.

On the basis of this risk assessment, the public health authority must carry out an incident-specific analysis before any operational measures are commenced. Other authorities are to be involved as required. In such a risk analysis, the following factors can be taken into account:

-

Number of persons affected

-

Mortality/lethality

-

Local spread

-

Likelihood of spread

-

Dynamics of spread

-

Type of agent (biological, chemical...)

Scenario-specific communication

For communication with partners, the general public and the press, it is essential in particular emergency scenarios to specify who is responsible for coordination and deciding which strategies are implemented, and which other authorities and institutions must be involved. It is also important to set out the fundamental objectives of communication, the specific content, the instruments employed in press work, and the target groups. (see chapter: Communications)

As well as communication with external partners, it is important to remember that staff of public authorities also have to be informed. In a crisis, everyone should have sufficient information in order to promote general understanding of the exceptional circumstances when the work situation is tense.

Alert system

In an emergency, the regional health authorities are generally notified (alerted) by the responsible coordination centres; (higher/lower) regional health authorities are often notified by central bodies, e.g. the police operations centre.

In the public health authorities, it is important to plan the internal alert and/or notification procedures for in-house staff and, if necessary, for other institutions that are to be involved. It makes sense to make use of existing alert systems in the authorities. Depending on the circumstances, it may be possible to set up alert contact groups at third parties, e.g. the fire service operations centre, so that staff at public health offices can be notified automatically without the need for further action. Alert and notification lists must be regularly updated. Alert drills can be used to test whether professional and private contact data are up to date.

Notification channels

When crisis-like incidents occur, the early recognition, validation and assessment of the situation is key to the rapid introduction of specific control and prevention measures. Pursuant to Article 6 of the International Health Regulations (IHR) and pursuant to Article 9 of Decision No. 1082/2013/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2013 on serious cross-border threats, Germany is legally obliged to immediately notify the international community of any events that may constitute a public health emergency of international concern or a serious cross-border threat to health. This notification provides early warning, as well as information for rapid assessment and early warning of all actors, and where appropriate joint coordination. It is provided by the public health office to the national (federal) authority, via the responsible regional authority.

The responsible national authority is

-

for biological events the RKI

-

for chemical events the BBK

-

for radiological/nuclear events the BMU.

For notifications of biological events the RKI provides a notification form; a form for notification of chemical hazards is provided by the BBK.

Pursuant to IHR Annex 2 (see Figure 2), cases of smallpox, poliomyelitis (due to wild-type poliovirus), human influenza (caused by a new subtype) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) must be notified.

'On 30 January 2020 the WHO declared the outbreak (of COVID-19) a public health emergency of international concern, and saw a compelling need to step up internationally coordinated efforts to control the outbreak in accordance with the International Health Regulations (IHR), also to better support countries with weaker health systems.' (COVID-19, information for employees and travellers, German Federal Foreign Office, 28 February 2020)

Cases of cholera, yellow fever, pneumonic plague, viral haemorrhagic fever or West Nile fever, as well as other events of potential international public health concern, must be notified to the WHO under certain circumstances.

The public health office notifies the national level via the competent regional authority if there is a mere possibility that an event might constitute a public health emergency of international concern according to the criteria of Annex 2 to the IHR.

The final assessment of whether an event must be notified to the World Health Organization or the competent authorities of the European Union is made by the competent national authority

Management structure

Staff at the public health authorities involved must be informed about the general management organisation structure in the case of large-scale emergencies and disasters (see chapter: Working in teams).

The operational plans of the public health authorities involved must specify who has management responsibility in particular scenarios. This responsibility must be clearly stated. If several authorities are involved, the areas of responsibility must be clearly defined.

In on-site assignments, it makes sense if the manager of the public health office can be recognised by all involved, e.g. by means of a vest.

Actors and tasks

Depending on the scenario, different actors – individuals and institutions – with different responsibilities will called on to respond to a particular incident. The operational plan must clearly show which actors are responsible for which tasks. It is also important to specify who is to coordinate particular tasks and which actors also play an active role.

Measures to be taken in an emergency

The measures undertaken depend on the respective scenario. A series of recommendations for action is presented in the toolbox of this textbook (see chapter: Toolbox).

Particular measures may be required by statutory regulations. In the public health services sector in Germany, these requirements follow from the Protection against Infection Act, the German Drinking Water Ordinance and the public health laws in the federal states. Other measures, also those not based on statutory requirements, must be specified individually in the operational plan.

Not all measures will necessarily be implemented in a real emergency scenario. On the other hand, other measures will be needed spontaneously and may not have been planned in advance.

The textbook's toolbox offers an array of options, from which the user can make the right selection as required. Measures that have not been documented/outlined must be flexibly organised and implemented by the responsible team.

Logistics and coordination

The coordination of logistics measures in an emergency can tie up many personnel. Test samples and disposal management for example can be considered as logistics tasks. For this reason, the focus of good operational planning should lie in this area in order to alleviate the burden in a crisis.

Resources

In some situations the resources required are provided by third parties These include hospital care facilities, the availability of vaccines and antidotes. Information on who will provide what, and when, should be included in operational plans, as making enquiries during a crisis costs a great deal of time and therefore must be avoided at all costs.

On the other hand, certain materials that are not available in an emergency or that may quickly be in short supply should be stocked by the health authorities. One important example is personal protective equipment (PPE).

Checklists for emergencies

One useful and important measure to keep things running smoothly are checklists that lay down in writing what information is required or needs to be obtained, and when. One good example is checklists in aviation, which pilots go through before take-off.

In a crisis, checklists enable us to act with confidence, which is important. They enable us to review our intuitive actions and check that the measures we have taken are complete. The handbook provides checklists at various points to support the heath authorities that need to act.